Sound of Sirens: First responders access to mental health resources in Oklahoma

There were still 186 miles to go, and Shelly Mack’s lungs were burning.

The average marathon is 26.2 miles, but Mack was doing the 340-mile-long marathon through the Volunteer State of Tennessee entirely of her own free will. Runners had 10 days to complete the race, using only the equipment they kept on themselves.

“We were sleeping on sidewalks, church porches,” Mack said. “You never knew when your next meal was going to be.”

Mack, 56, said this marathon in particular was one of her favorite’s she’s done. A distance that takes almost five hours to drive was done in a little over a week across the deep south. She has done this marathon three times now, with the first in 2015, totaling more than 1,000 miles in those three runs alone. For an Oklahoma girl, this was no easy task.

Shelly Mack and her daughter, Whitley Kokojan, in Tennessee Courtesy of Whitley Kokojan

at the first 340-mile-long marathon in Mack's running career.

“You really appreciate the things that you have when you get home,” she said.

This couldn’t be more true for Mack’s daughter, Whitley Kokojan, who Mack has always supported. Kokojan said there isn’t much her mother isn’t willing to do for her family and those around her.

“My mom always would give the skin off her back for any one of us kids,” Kokojan said. “She’s a giver, tried and true.”

Mack uses running to improve her mental health and cope with the job she has. She is currently an infection preventionist for Integris Hospital in Enid, Oklahoma, but has worked in a variety of roles including an emergency room nurse and a special ed teacher. Mack said she would go crazy if she wasn’t able to do the running she does, especially with the career she’s had for the previous two decades.

“I literally have to wear myself out physically before I can mentally say I'm OK,” she said.

Shelly Mack during her second Courtesy of Whitley Kokojan

time running the 340-mile-long

marathon by herself while holding

a photo of her daughter as a child.

Being an ER nurse comes with its caveats. Burnout is a large problem in nurses, especially in the emergency room or with psych nurses, and it has only gotten worse since COVID-19. Mack uses running to cope with the stresses of the job, but she said everyone else is not as lucky. She said mental health resources in the state of Oklahoma are not good, not only for first responders and nurses but citizens in general.

“Awful, absolutely horrible,” said Mack, talking about the access to mental health help in the state. “The patients were in the hospital in our ER for hours upon hours before we could ever get them moved to a mental health facility. I know even today there are times in our little ER that we hold three and four mental health patients ranging from little kids to adults, trying to find them placement, and a lot of times we have to send them to Texas or Kansas and other things.”

She said the coverage for the people on the job is not great either. Nurses get six free sessions with a counselor a year, but anything after that, insurance only covers so much. Mack said it gets expensive if a nurse wants to actively seek mental health support. Burnout has been a large cause of nurses and other medical personnel switching jobs.

Madison Welch, a registered nurse in Enid, said she has similar sentiments to hospital administration's support of staff. She said it plays a big part in mental health when they are short staffed and upper management says, “Well, that’s just how it is.”

“It's exhausting,” Welch said. “It's easy to get burnt out. Not only because you have long days, but you're in charge of these people's lives.”

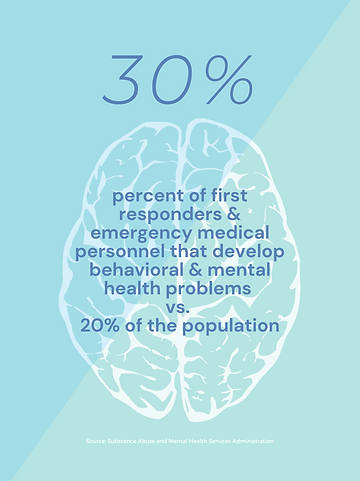

About 30% of first responders and other emergency medical personnel develop behavioral health conditions or mental health issues including depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) compared to 20% of the general population, according to a report by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Claire Thomas & Lindsey Heitte

Nurses across the state are continuing to deal with the lack of mental health support from administration and the government.

“It's just really heartbreaking to see people sob over their loved ones and beg God for them to come back.”

-Rachel Clanton

Rachel Clanton is a registered nurse in Tulsa and works in the ICU. She said it’s hard to work in healthcare because workers get so desensitized to things that would normally bother other people. Clanton started nursing after COVID-19 began but when the nation was still in the height of quarantine. Clanton said the workload, on top of saving people’s lives, makes mental health worse.

Rachel Clanton and her coworker MaKayla Keirsey

“I think in the first three months of working at the hospital, I lost three pounds just from not eating,” she said. “I was constantly stressed out with the workload and with not being able to find enough time to take care of the people that were so sick.

“It kind of made me question what am I doing, you know, in healthcare.”

Clanton went on to talk about mental health in Oklahoma and the access staff have to it. She said the administration never talked about mental health, even in the heat of COVID-19, and upper management doesn’t offer the best support when it comes to trauma processing.

“It's just really heartbreaking to see people sob over their loved ones and beg God for them to come back," Clanton said.

The business side of a hospital also causes conflict. Clanton talked about the differences in the types of hospital employees. She said at the end of the day a hospital is still a business and the upper management cares a lot about money.

“You know, I mean, no matter what hospital you go to, no matter how many times you're told, ‘You're not a number you're a person,’ whatever it comes down to, it's a business,” Clanton said. “And so it's hard to look at it from both sides because my job is so emotionally involved. I love it. I love it so much. I really do. It's just frustrating. Because you're being controlled by upper management who've never worked at the bedside.”

Every county in the state is facing a shortage of mental health providers, according to a report from the federal Health Resources and Services Administration. Welch said it shows in the faces of first responders most days.

“I feel like nursing, at least for me, you know, I see a lot of different mental health crises, especially depression and anxiety,” Welch said. “And I think that we get jaded sometimes.”

Emergency responders often push MaKayla Keirsey

their own mental health aside

to help others.

Welch said mental health is not given enough importance in the state, especially in smaller towns with fewer hospitals and less funding. Rural areas are even harder to get comprehensive mental health access to, and those areas make up most of the state.

“I feel like in our world it’s so much living to work instead of working to live,” Welch said.

Outside of the hospital itself, EMTs also have a hard time coping with the situations on the job. Oklahoma EMS conducted a Health and Wellness Survey that showed PTSD risk factors and EMTs exposure to it. The majority of survey respondents that showed high risk factors to PTSD were undiagnosed by a healthcare professional. Barriers to a diagnosis included professional stigma at 10%.

"You kind of just reach a point. You just are like, ‘Well, nobody cares, so why should I?’"

-Madison Welch

Austin Perry is a senior technician supervisor at Work Health Solutions in Tulsa but was an EMT right after high school in 2017. He worked for five years at LifeNet in Stillwater. He knew he wasn’t going to do a traditional college career and decided he wanted to do something that involved using his hands. Perry was around retired paramedics and heard their stories. He knew then he wanted to be a paramedic.

“I was raised as a pretty sheltered kid,” Perry said. “My first year was definitely a pretty big adjustment period. I saw a lot of stuff that I had no idea existed in the world. It was pretty eye opening.”

Perry said he would have long hours, 12-24, with little to no breaks in between. He also said that he took too many of these calls at a time where he would have to be compassionate or empathetic toward people, which evidently caused him to quit.

Before working as an EMT, Perry didn't think about mental health much. When he was working there, he said there was a stigma around it in their field. Perry said people who had mental health concerns were quickly called “crazy and unreliable.”

Katie Perry, Austin Perry’s wife, is also a first responder. She is a full-time nurse at St. Francis in the trauma center and a part-time EMT driver.

She said she loved medicine and knew she wanted to do something in that field, but she didn’t know what. When Austin was getting his EMT license, she would help him study for his test and knew afterward that she liked it.

Katie said she has had a lot of anxiety for a while now, and her position as an EMT didn’t help her mental health. She said there were certain calls that would remind her of specific family members that emotionally got to her.

One story that affected her health was when she was in college at OSU and took a call in Stillwater. There was an accident that caused two best friends in the vehicle to tip, killing the passenger who was not wearing a seatbelt.

When her partner and she arrived on the scene, the best friend was trying to do CPR on the victim, but it was too late. Katie had to be the one to tell her to stop because her friend was dead.

“For some reason, instead of normally just being able to brush it off and call it a workday, I think that's the first time that I really cried from a call and it made me sad,” Katie said.

Katie said no one was required to go to mental health therapy and in order to get therapy, she had to admit she was affected by the call. She didn’t want to admit it. The majority of survey respondents, 67%, that indicated risk factors for PTSD said they simply didn’t need help, according to the survey report from Oklahoma EMS. Katie said there were a lot of people in EMS who committed suicide because of the calls they dealt with.

A majority of first responders struggle with some MaKayla Keirsey

form of mental health.

Welch said it’s hard to push yourself to care and be happy when it seems like no one else is. She has struggled with transitioning back into work life since giving birth to her son and said it’s difficult to find the motivation, especially with how mentally taxing the job is.

"You kind of just reach a point," she said. "You just are like, ‘Well, nobody cares, so why should I?’"

Hospital waiting rooms see some of the most MaKayla Keirsey

traumatic events in a person's life and nurses

and first responders have to witness it daily.